USA TODAY: 'It's been hell': Parents struggle with distance learning for their kids with disabilities

date:2020-05-25 21:25author:小编source:USA TODAYviews:

DELAND, Fla. – Malika Simmons couldn’t believe her eyes when she received the schoolwork for her son to do at home during the coronavirus pandemic.

Eli Simmons, 12, who has autism spectrum disorder and severe learning disabilities, usually works with a team of four professionals each day at River Springs Middle School in Orange City, Florida. He’s still learning his letters and numbers.

The packet of work they received was filled with lessons on how to write a check and how to identify different angles – things that are miles beyond Eli’s ability.

In those early weeks of remote learning in March and April, Simmons hadn’t heard much from her son's teacher and one-on-one paraprofessional, so she scoured Walmart for learning games that she couldn’t really afford. She worked on his number recognition and handwriting, in between trying to keep him from literally pulling up the carpet. Most days, she has to bribe him just to sit still.

“It’s been hell,” she said.

Like parents across the country with school-age children, Simmons has been trying to keep her head above water. For weeks, students have been forced into new forms of learning by the coronavirus pandemic. Distance learning will continue through the end of the school year in most states.

Adjustments that might be rough on their peers are even harder for the millions of students with disabilities, many of whom depend on additional support and therapy at school sites that they may be missing.

Behavioral therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, physical therapy, the attention of paraprofessionals and intervention teachers and support facilitation teachers – it's all the parents' responsibility now. When those services can be offered virtually, parents must still facilitate the meetings, supervise and try to schedule it all in. Families wonder how educators will make up the lost ground in the fall.

Heather Dorries is a stay-at-home mom in Palm Coast, Florida, with three kids with special needs, ranging from autism spectrum disorder to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder to physical impairments. It was so difficult to keep up with their ever-changing, often conflicting schedules, she decided to temporarily ask the school to suspend their support therapies and effectively forfeit their right to make up their missed services when school returns – a move she worries will disrupt their development but one she felt she had to make.

“I’m having to sit back and decide, is it worth it? What is more important at this point – these therapies or for them to complete school work?” she said. “There just aren’t enough hours in the day for me. You’re just one person.”

Eli Simmons, 12, who has autism spectrum disorder and severe learning disabilities, usually works with a team of four professionals each day at River Springs Middle School in Orange City, Florida. He’s still learning his letters and numbers.

The packet of work they received was filled with lessons on how to write a check and how to identify different angles – things that are miles beyond Eli’s ability.

In those early weeks of remote learning in March and April, Simmons hadn’t heard much from her son's teacher and one-on-one paraprofessional, so she scoured Walmart for learning games that she couldn’t really afford. She worked on his number recognition and handwriting, in between trying to keep him from literally pulling up the carpet. Most days, she has to bribe him just to sit still.

“It’s been hell,” she said.

Like parents across the country with school-age children, Simmons has been trying to keep her head above water. For weeks, students have been forced into new forms of learning by the coronavirus pandemic. Distance learning will continue through the end of the school year in most states.

Adjustments that might be rough on their peers are even harder for the millions of students with disabilities, many of whom depend on additional support and therapy at school sites that they may be missing.

Behavioral therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, physical therapy, the attention of paraprofessionals and intervention teachers and support facilitation teachers – it's all the parents' responsibility now. When those services can be offered virtually, parents must still facilitate the meetings, supervise and try to schedule it all in. Families wonder how educators will make up the lost ground in the fall.

Heather Dorries is a stay-at-home mom in Palm Coast, Florida, with three kids with special needs, ranging from autism spectrum disorder to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder to physical impairments. It was so difficult to keep up with their ever-changing, often conflicting schedules, she decided to temporarily ask the school to suspend their support therapies and effectively forfeit their right to make up their missed services when school returns – a move she worries will disrupt their development but one she felt she had to make.

“I’m having to sit back and decide, is it worth it? What is more important at this point – these therapies or for them to complete school work?” she said. “There just aren’t enough hours in the day for me. You’re just one person.”

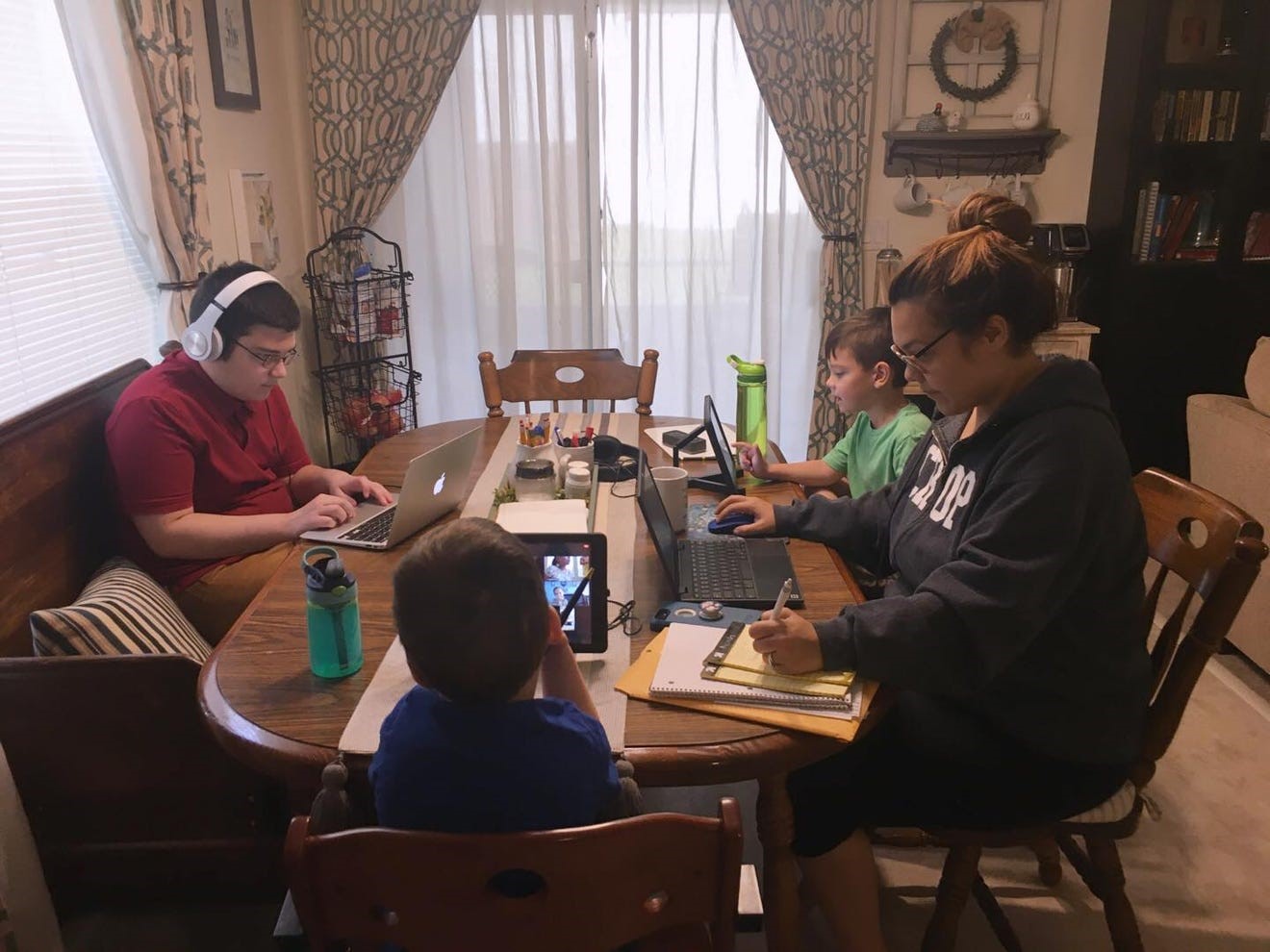

Heather Dorries works alongside her three children in their Palm Coast, Fla., home. Each child has disabilities that require special services from their schools, but when school is the dining room table, Dorries says, it feels near impossible for her to keep up with everything.

Learning to adjust

As the coronavirus spread across the country, districts took different approaches to learning. In most Florida districts, the plan has been to forge ahead with materials in a new format.

Those plans came together in a matter of weeks when developing effective, comprehensive virtual school programs usually takes much more time.

Liz Kolb, a professor of education technologies and teacher education at the University of Michigan, told USA TODAY that online learning and virtual instruction can increase gaps in equity. Learning to bridge those gaps takes time.

“Most virtual schools are able to make these accommodations, but they have had years to put these supports in place,” she said. “Traditional face-to-face schools are aware they need to do this, but they may still be working on the ‘how.’ ”

That’s what Katie Kelly, a civil rights attorney from Community Legal Services of Mid-Florida, has seen with her clients. Kelly said the system that results from at-home learning isn’t fair for families who are entitled under federal law to a free, equitable education.

“None of this is free or appropriate if you’re having to do the work of a teacher,” Kelly said. “And none of this is free or appropriate if you’re having to educate your child by yourself.”

Directors of exceptional student education explained that they did not expect significant disruptions in the services they were providing to students and families. Some evaluations must be postponed, some services modified, but overall, they expected to rise to the new challenges caused by the pandemic.

“We do not expect the parents to replace teachers or related service providers, but we do want and need to partner with them,” said Kim Gilliland, the director of exceptional student education in Volusia County, where Eli Simmons is enrolled. “These unprecedented times have changed the look of educational services, but it is our goal to ensure that it does not stop the students from learning.”

For students who do fall behind, Kelly said, schools are required to offer remediation for time or services lost. Gilliland said that based on federal guidance, the teams who create the individualized education plans for students with special needs will make those determinations as well.

“No plan is ever foolproof,” Gilliland said, “but we are doing our best.”

The parents who spoke to The Daytona Beach News-Journal worry that it won't be enough for their children.

Those plans came together in a matter of weeks when developing effective, comprehensive virtual school programs usually takes much more time.

Liz Kolb, a professor of education technologies and teacher education at the University of Michigan, told USA TODAY that online learning and virtual instruction can increase gaps in equity. Learning to bridge those gaps takes time.

“Most virtual schools are able to make these accommodations, but they have had years to put these supports in place,” she said. “Traditional face-to-face schools are aware they need to do this, but they may still be working on the ‘how.’ ”

That’s what Katie Kelly, a civil rights attorney from Community Legal Services of Mid-Florida, has seen with her clients. Kelly said the system that results from at-home learning isn’t fair for families who are entitled under federal law to a free, equitable education.

“None of this is free or appropriate if you’re having to do the work of a teacher,” Kelly said. “And none of this is free or appropriate if you’re having to educate your child by yourself.”

Directors of exceptional student education explained that they did not expect significant disruptions in the services they were providing to students and families. Some evaluations must be postponed, some services modified, but overall, they expected to rise to the new challenges caused by the pandemic.

“We do not expect the parents to replace teachers or related service providers, but we do want and need to partner with them,” said Kim Gilliland, the director of exceptional student education in Volusia County, where Eli Simmons is enrolled. “These unprecedented times have changed the look of educational services, but it is our goal to ensure that it does not stop the students from learning.”

For students who do fall behind, Kelly said, schools are required to offer remediation for time or services lost. Gilliland said that based on federal guidance, the teams who create the individualized education plans for students with special needs will make those determinations as well.

“No plan is ever foolproof,” Gilliland said, “but we are doing our best.”

The parents who spoke to The Daytona Beach News-Journal worry that it won't be enough for their children.

Pressure on parents

Paige Auborn, 26, was a little nervous when she found out schools were going to close. Anyone would be, with nine kids ages 2 to 20, five of whom are on the autism spectrum. All of the children are adopted, six by her mother and three by her, and they all live under one roof.

As a paraprofessional and after years of experience working with foster children with special needs, she thought she would be well-suited for educating them at home.

The first challenge arose when her immunocompromised mother felt ill and had to stay in another location, lest she risk catching or spreading the coronavirus. She stayed away even after she got better because of all the therapists and specialists coming in and out of the house. She’s starting to come back to the house, but even with an extra adult around, it’s difficult to keep so many kids at different levels on track academically.

Weeks of distance learning came with a couple of meltdowns – one of which was so volatile the family had to call law enforcement, who took the child for an involuntary psychological examination under Florida's Baker Act.

Auborn has tried to adopt a more relaxed attitude toward the children's schooling. Between virtual visits with therapists, printed and digital materials spanning multiple grades and the regular work involved in running a huge household, following the schools’ instructions to the letter is not a priority for their family.

“I don’t have a college degree in teaching, and overnight, I became a VPK, kindergarten, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh grade teacher,” she said, plus a special education teacher for students of varying abilities. “If I can’t get it all completed, if they’re trying their hardest, that’s the best we can do right now.”

Hospice nurse Michelle Sammons in Flagler County has four kids at home, three of whom receive special education services from their schools. She counted 14 teachers or therapists who normally work with them. She’s replacing them all.

“I worry a lot about them because they’re already behind. How they’re going to get caught up? I don’t know,” Sammons said. “It’s really been a challenge.”

Dorries, the Palm Coast mother, said she felt she had no other choice but to suspend her children’s services, even though she worries about how it will affect them.

“There are days when it has been OK,” she said, “and there’s been some days where I want to just go to bed at 4 p.m. and cry myself to sleep.”

Source:https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/05/22/coronavirus-parents-distance-learning-woes-kids-disabilities/5227887002/

As a paraprofessional and after years of experience working with foster children with special needs, she thought she would be well-suited for educating them at home.

The first challenge arose when her immunocompromised mother felt ill and had to stay in another location, lest she risk catching or spreading the coronavirus. She stayed away even after she got better because of all the therapists and specialists coming in and out of the house. She’s starting to come back to the house, but even with an extra adult around, it’s difficult to keep so many kids at different levels on track academically.

Weeks of distance learning came with a couple of meltdowns – one of which was so volatile the family had to call law enforcement, who took the child for an involuntary psychological examination under Florida's Baker Act.

Auborn has tried to adopt a more relaxed attitude toward the children's schooling. Between virtual visits with therapists, printed and digital materials spanning multiple grades and the regular work involved in running a huge household, following the schools’ instructions to the letter is not a priority for their family.

“I don’t have a college degree in teaching, and overnight, I became a VPK, kindergarten, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh grade teacher,” she said, plus a special education teacher for students of varying abilities. “If I can’t get it all completed, if they’re trying their hardest, that’s the best we can do right now.”

Hospice nurse Michelle Sammons in Flagler County has four kids at home, three of whom receive special education services from their schools. She counted 14 teachers or therapists who normally work with them. She’s replacing them all.

“I worry a lot about them because they’re already behind. How they’re going to get caught up? I don’t know,” Sammons said. “It’s really been a challenge.”

Dorries, the Palm Coast mother, said she felt she had no other choice but to suspend her children’s services, even though she worries about how it will affect them.

“There are days when it has been OK,” she said, “and there’s been some days where I want to just go to bed at 4 p.m. and cry myself to sleep.”

Source:https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/05/22/coronavirus-parents-distance-learning-woes-kids-disabilities/5227887002/